Often when we think about Head Start history, we recall the White House Rose Garden Ceremony on May 18, 1965 in which President Johnson announced Project Head Start. But this was only the beginning. Following that historic day, it took the work of determined community leaders, many of them Civil Rights advocates ready to challenge the status quo, to build Head Start into the life-changing force we know. Launching an integrated, anti-poverty program at the peak of the Modern Civil Rights Movement was met with much resistance. We owe the leaders, teachers, and parents who persisted a wealth of gratitude. In honor of Black History Month, we reflect on just how deeply intertwined Head Start’s history is with that of the Civil Rights Movement.

In her book, A Chance for Change: Head Start and Mississippi’s Black Freedom Struggle, historian Crystal Sanders explores the history of the Child Development Group of Mississippi’s (CDGM) Head Start program. CDGM was a community action program under the Economic Opportunity Office—Head Start’s original home office in the federal government—and it brought together many Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and NAACP activists in its leadership. These leaders had the experience and the desire to put the goals of the Civil Rights Movement into action through early childhood education. Sanders wrote:

“They translated a grassroots educational endeavor into an opportunity to better themselves, their communities, and their children’s futures.”

From the beginning, family and community involvement were at the foundation of Head Start’s model. In Mississippi in 1965 this meant that parents, Black mothers in particular, had unprecedented opportunities to shape their children’s education which was, as Sanders notes, “an opportunity denied to them in the public school system that was under white supervision.” Not only were parents able and encouraged to play a role in their children’s education through CDGM, but many also gained employment as administrators, teachers, and cooks.

There were also obstacles to be overcome at every turn. In that first year, for example, not one school superintendent rented out school buildings or buses to CDGM, leaving them to source resources elsewhere in the community and build from scratch. Despite this unwillingness to embrace integration and progress from institutions in the community, Head Start persisted.

The Child Development Group of Mississippi, Head Start, 1965. Photographer: Bob Fletcher

Also in Head Start’s inaugural year, a young Darren Walker, now president of the Ford Foundation, was enrolled in a Texas program.

“I was raised by a single mother, and my sister and I lived in the early 1960s in a small town in East Texas called Ames—what one in those days called the colored community,” Walker recalls. “The scene is a little dirt road with a modest shotgun shack, and a woman approached my mother and me on the porch and told my mother about a new government program called Head Start.”

Six decades later, Mr. Walker believes his own work aligns with that of the Head Start program that gave him his start—both in the business of hope and of opportunity.

Darren Walker is a prominent example. But he is just one of many examples of Head Start’s impact for low-income Black children who grew up in the 1960s. We know that the work of Civil Rights leaders running CDGM, of the woman who approached Darren Walker’s mother, and of countless others made an impact—we know because we see Head Start alumni leading in every field, in every community today.

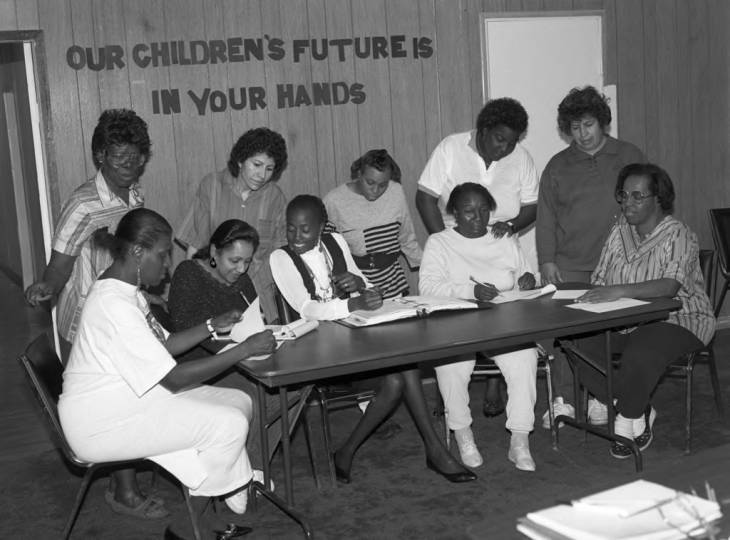

Urban League Head Start, Los Angeles, 1991. Photographer: Guy Crowder

Head Start owes its birth and early development deeply to the determination and tenacity of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. During Black History Month, we reflect on this relationship between Head Start and the Civil Rights Movement, and how this legacy lives on today.

Related Content