The work of early childhood educators improves the social, behavioral, and academic development of young children, providing a foundation for success in school and in life. Yet, the early childhood workforce—predominantly made up of women of color—continues to be undervalued and underpaid. The pay gap remains a formidable barrier to a strong and sustained early childhood workforce that can effectively partner with children and families. Advocates in the field have been calling for fair wages for many decades, yet the problem persists. To fully understand the scope of this challenge, leaders in early childhood must look more deeply at the lack of salary parity—equal pay for equal or comparable work—especially across setting and race.

Exploring Pay Gaps by Setting

One of the more notable and recognized pay gaps exists between private preschool providers and K-3 teachers. Public school kindergarten teachers make upwards of $30,000 more than their private preschool educator counterparts, although they teach similar skills and perform similar tasks. Degree requirements and unionization explain some of this gap, but certainly not all. Even in settings like Head Start, where lead teachers are required to have bachelor’s degrees and many obtain masters or other advanced credentials, the gap is wide.

Exploring Pay Gaps by Race

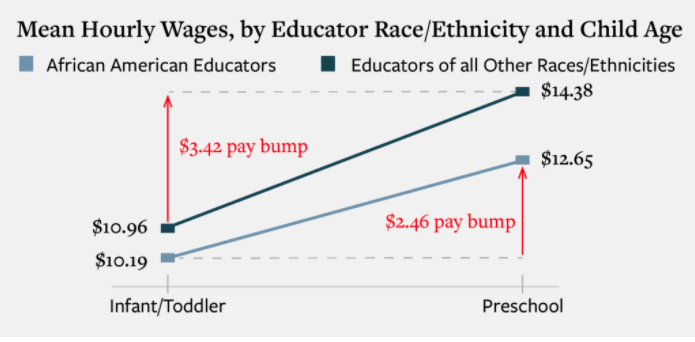

Source: UC Berkeley, Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, Dec. 2019

Digging deeper, the racialized wage differentials that exist among the early childhood workforce are alarming. In 2019, Black infant educators were paid nearly a dollar less per hour than the already low wage of their non-Black counterparts. At the preschool level, the wage discrepancy was even steeper. The data makes clear that there exists a significant lack of salary parity between preschool teachers and K-3 teachers that is exacerbated and compounded by race.

Why Does the Pay Gap Exist?

What can explain these racialized wage gaps in the early childhood sector? One driver that has received too little attention is unconscious racial bias. Ideas influence infrastructure. Infrastructure upholds and perpetuates systemic racism. Human resources (HR) departments are key systems in education. Unconscious bias influences perceptions of workers’ value, efficacy, and thus, compensation rates.

What Can We Do

It would be reductive and fruitless to strive to make these HR systems neutral; biases are deep-rooted and ever-evolving. What we can do is develop proactive and consistent policies that shine a light on the biases occurring.

To increase accountability, there needs to be transparent data collection of educator and staff wages based on demographics to determine the racial wage gaps occurring, to analyze if there are experience and educational factors at work, and to determine the appropriate next steps. Data collection would shed a light on areas of improvement for organizations.

Head Start has certainly taken strides to promote such transparency. The National Head Start Association was a lead participant in the Power to the Profession task force, which has developed frameworks for addressing equitable compensation for early childhood educators. Along the lines of clarifying governance structures, which would in turn improve data collection efforts, the task force has recommended the intentional consolidation of educator designations based on level of mastery and professional preparation. However, professional preparation can be inaccessible at times.

In the ECE field, we want to ensure all educators are effectively prepared and have the competencies necessary to support strong outcomes for children. Recruitment and hiring efforts need to recognize and factor in the explicit and hidden costs associated with increasing one’s educational credentials coupled with the systemic wealth inequality that disproportionately impacts Black, Indigenous, and people of color in the U.S. This stark wealth gap looms over the feasibility of higher education for educators of color and factors into conversation about racial pay gaps when looking at how higher compensation for higher education credentials is levied.

The Challenges in Achieving Salary Parity

One of the concerns about achieving salary parity within ECE and with K-3 teachers is the feasibility of financing these reforms. Questions of “How will we afford this?” often arise. State responses to the child care crisis precipitated by COVID-19 show the funding barrier to salary parity can be overcome with a combination of federal and state support. Many states have increased reimbursement rates to providers temporarily and offered hazard pay to ECE teachers.

From previous experience, we also know that federal and state funding has been successfully layered to reach parity standards for educators. The question lies in how willing the federal and state governments are to invest in early childhood education and the professionals that care for and educate our youngest children.

The future of pay equity in ECE

Given their role in funding state pre-K, it falls largely on states to look hard at this system and demand equal pay for equal work across settings and by race. A handful of states are already enacting laws supportive of early educators. New Mexico offers loan forgiveness for ECE educators, understanding the cost of higher education and student debt is a particular barrier for teachers of color. Connecticut is also developing an early educator compensation schedule that extends beyond pre-K. This approach will naturally reach into settings where teachers of color predominate, including infant and toddler settings.

As a field, we can close these pay gaps. The best advocates for these changes have come from within the Head Start and ECE community. Last year, the mayor of New York City approved a contract to raise the salaries of early childhood educators, including Head Start teachers, over the course of three years. Originally, Head Start teachers were not included in the conversation with the other unionized teachers. However, once a part of the dialogue, they were able to secure $12,800-$15,000 increases for teachers and staff. This shows how forming broad coalitions and engaging in conversations with other sectors, can create invaluable opportunities to impact decision-makers as it relates to ECE pay gaps.

This is not to say that the burden for securing salary parity should rest upon the shoulders of our educators who are already diligently committed to educational preparation and teaching. Rather, this example demonstrates that coalescing and advocacy does work. Our educators’ voices can weigh in and shape the trajectory of equity within the workforce.

The ECE workforce is comprised almost exclusively of women, 40 percent of whom are people of color, which means there are intersectional biases at play. Confronting these biases and addressing pay equity in ECE is critical to building a strong, financially-stable workforce with less turnover. It will allow stronger bonds to form between teachers and children. It will allow early educators of color to make a liveable wage in the profession they love.

Related Content